The courts of appeals receive less media coverage than the Supreme Court, but they are very important in the U.S. judicial system. Considering that the Supreme Court hands down decisions with full opinions in only 80 to 90 cases each year, it is apparent that the courts of appeals are the courts of last resort for most appeals in the federal court system. [1]

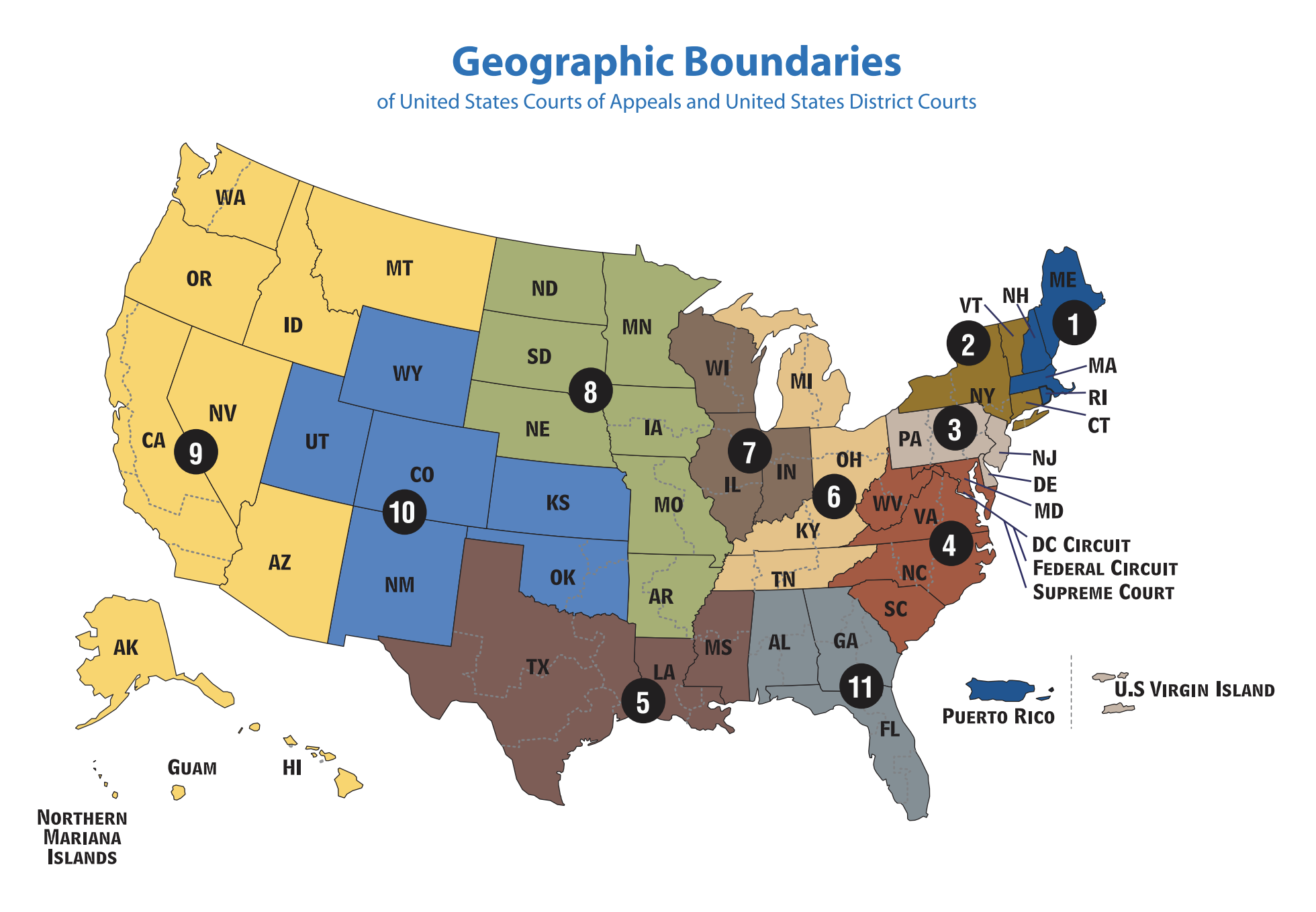

The 94 federal judicial districts are organized into 12 regional circuits, each of which has a court of appeals. The appellate court’s task is to determine whether or not the law was applied correctly in the trial court. Appeals courts consist of three judges and do not use a jury.

A court of appeals hears challenges to district court decisions from courts located within its circuit, as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies.

In addition, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has nationwide jurisdiction to hear appeals in specialized cases, such as those involving patent laws, and cases decided by the U.S. Court of International Trade and the U.S. Court of Federal Claims.

At a trial in a U.S. District Court, witnesses give testimony and a judge or jury decides who is guilty or not guilty — or who is liable or not liable. The appellate courts do not retry cases or hear new evidence. They do not hear witnesses testify. There is no jury. Appellate courts review the procedures and the decisions in the trial court to make sure that the proceedings were fair and that the proper law was applied correctly.

An appeal is available if, after a trial in the U.S. District Court, the losing side has issues with the trial court proceedings, the law that was applied, or how the law was applied. Generally, on these grounds, litigants have the right to an appellate court review of the trial court’s actions. In criminal cases, the government does not have the right to appeal.

The reasons for an appeal vary. However, a common reason is that the dissatisfied side claims that the trial was conducted unfairly or that the trial judge applied the wrong law, or applied the law incorrectly. The dissatisfied side may also claim that the law the trial court applied violates the U.S. Constitution or a state constitution.

The side that seeks an appeal is called the petitioner. It is the side that brings the petition (request) asking the appellate court to review its case. The other side is known as the respondent. It is the side that comes to court to respond to and argue against the petitioner’s case.

Before lawyers come to court to argue their appeal, each side submits to the court a written argument called a brief. Briefs can actually be lengthy documents in which lawyers lay out the case for the judges prior to oral arguments in court. [1] Additional information below.

*********************************

U.S. Court of Appeal for the Federal Circuit Official Website

*********************************

Map from UScourts.gov

click to enlarge

*********************************

The Review Function

of the Courts of Appeals:

Most of the cases reviewed by the courts of appeals originate in the federal district courts. Litigants disappointed with the lower-court decision may appeal the case to the court of appeals of the circuit in which the federal district court is located. The appellate courts have also been given authority to review the decisions of certain administrative agencies.

Because the courts of appeals have no control over which cases are brought to them, they deal with both routine and highly important matters. At one end of the spectrum are frivolous appeals or claims that have no substance and little or no chance for success. At the other end of the spectrum are the cases that raise major questions of public policy and evoke strong disagreement. Decisions by the courts of appeals in such cases are likely to establish policy for society as a whole, not just for the specific litigants. Civil liberties, reapportionment, religion, and education cases provide good examples of the kinds of disputes that may affect all citizens.

There are two purposes of review in the courts of appeals. The first is error correction. Judges in the various circuits are called upon to monitor the performance of federal district courts and federal agencies and to supervise their application and interpretation of national and state laws. In doing so, the courts of appeals do not seek out new factual evidence, but instead examine the record of the lower court for errors. In the process of correcting errors the courts of appeals also settle disputes and enforce national law.

The second function is sorting out and developing those few cases worthy of Supreme Court review. The circuit judges tackle the legal issues earlier than the Supreme Court justices and may help shape what they consider review-worthy claims. Judicial scholars have found that appealed cases often differ in their second hearing from their first.

The Courts of Appeals as Policy Makers:

The Supreme Court‘s role as a policy maker derives from the fact that it interprets the law, and the same holds true for the courts of appeals. The scope of the courts of appeals’ policy-making role takes on added importance, given that they are the courts of last resort in the vast majority of cases.

As an illustration of the far-reaching impact of circuit court judges, consider the decision in a case involving the Fifth Circuit. For several years the University of Texas Law School (as well as many other law schools across the country) had been granting preference to African American and Mexican American applicants to increase the enrollment of minority students. This practice was challenged in a federal district court on the ground that it discriminated against white and nonpreferred minority applicants in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. On March 18, 1996, a panel of Fifth Circuit judges ruled in Hopwood v. Texas that the Fourteenth Amendment does not permit the school to discriminate in this way and that the law school may not use race as a factor in law school admissions. The U.S. Supreme Court denied a petition for a writ of certiorari in the case, thus leaving it the law of the land in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, the states comprising the Fifth Circuit. Although it may technically be true that only schools in the Fifth Circuit are affected by the ruling, an editorial in The National Law Journal indicates otherwise, noting that while some “might argue that Hopwood’s impact is limited to three states in the South…, the truth is that across the country law school (and other) deans, fearing similar litigation, are scrambling to come up with an alternative to affirmative action.“

The Courts of Appeals at Work:

The courts of appeals do not have the same degree of discretion as the Supreme Court to decide whether to accept a case. Still, circuit judges have developed methods for using their time as efficiently as possible.

Screening – During the screening stage the judges decide whether to give an appeal a full review or to dispose of it in some other way. The docket may be reduced to some extent by consolidating similar claims into single cases, a process that also results in a uniform decision. In deciding which cases can be disposed of without oral argument, the courts of appeals increasingly rely on law clerks or staff attorneys. These court personnel read petitions and briefs and then submit recommendations to the judges. As a result, many cases are disposed of without reaching the oral argument stage.

Three-Judge Panels – Those cases given the full treatment are normally considered by panels of three judges rather than by all the judges in the circuit. This means that several cases can be heard at the same time by different three-judge panels, often sitting in different cities throughout the circuit.

En Banc Proceedings – Occasionally, different three-judge panels within the same circuit may reach conflicting decisions in similar cases. To resolve such conflicts and to promote circuit unanimity, federal statutes provide for an “en banc” (Old French for high seat)procedure in which all the circuit’s judges sit together on a panel and decide a case. The exception to this general rule occurs in the large Ninth Circuit where assembling all the judges becomes too cumbersome. There, en banc panels normally consist of 11 judges. The en banc procedure may also be used when the case concerns an issue of extraordinary importance.

Oral Argument – Cases that have survived the screening process and have not been settled by the litigants are scheduled for oral argument. Attorneys for each side are given a short amount of time (as little as 10 minutes) to discuss the points made in their written briefs and to answer questions from the judges.

The Decision – Following the oral argument, the judges may confer briefly and, if they are in agreement, may announce their decision immediately. Otherwise, a decision will be announced only after the judges confer at greater length. Following the conference, some decisions will be announced with a brief order or per curiam opinion of the court. A small portion of decisions will be accompanied by a longer, signed opinion and perhaps even dissenting and concurring opinions. Recent years have seen a general decrease in the number of published opinions, although circuits vary in their practices.

Circuit Courts: 1789-1891:

The Judiciary Act of 1789 created three circuit courts (courts of appeals), each composed of two justices of the Supreme Court and a district judge. The circuit court was to hold two sessions each year in each district within the circuit. The district judge became primarily responsible for establishing the circuit court’s workload. The two Supreme Court justices then came into the local area and participated in the cases. This practice tended to give a local rather than national focus to the circuit courts.

The circuit court system was regarded from the beginning as unsatisfactory, especially by Supreme Court justices, who objected to the traveling imposed upon them. Attorney General Edmund Randolph and President Washington urged relief for the Supreme Court justices. Congress made a slight change in 1793 by altering the circuit court organization to include only one Supreme Court justice and one district judge. In the closing days of President John Adams’s administration in 1801, Congress eliminated circuit riding by the Supreme Court justices, authorized the appointment of 16 new circuit judges, and greatly extended the jurisdiction of the lower courts.

The new administration of Thomas Jefferson strongly opposed this action, and Congress repealed it. The Circuit Court Act of 1802 restored circuit riding by Supreme Court justices and expanded the number of circuits. However, the legislation allowed the circuit court to be presided over by a single district judge. Such a change may seem slight, but it proved to be of great importance. Increasingly, the district judges began to assume responsibility for both district and circuit courts. In practice, then, original and appellate jurisdiction were both in the hands of the district judges.

The next major step in the development of the courts of appeals did not come until 1869, when Congress approved a measure that authorized the appointment of nine new circuit judges and reduced the Supreme Court justices’ circuit court duty to one term every two years. Still, the High Court was flooded with cases because there were no limitations on the right of appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Courts of Appeals: 1891 to the Present:

On March 3, 1891, the Evarts Act was signed into law, creating new courts known as circuit courts of appeals. These new tribunals were to hear most of the appeals from district courts. The old circuit courts, which had existed since 1789, also remained. The new circuit court of appeals was to consist of one circuit judge, one circuit court of appeals judge, one district judge, and a Supreme Court justice. Two judges constituted a quorum in these new courts.

Following passage of the Evarts Act, the federal judiciary had two trial tribunals: district courts and circuit courts. It also had two appellate tribunals: circuit courts of appeals and the Supreme Court. Most appeals of trial decisions were to go to the circuit court of appeals, although the act also allowed direct review in some instances by the Supreme Court. In short, creation of the circuit courts of appeals released the Supreme Court from many petty types of cases. Appeals could still be made, but the High Court would now have much greater control over its own workload. Much of its former caseload was thus shifted to the two lower levels of the federal judiciary.

The next step in the evolution of the courts of appeals came in 1911. In that year Congress passed legislation abolishing the old circuit courts, which had no appellate jurisdiction and frequently duplicated the functions of district courts.

Today the intermediate appellate tribunals are officially known as courts of appeals, but they continue to be referred to colloquially as circuit courts. There are now 12 regional courts of appeals, staffed by 179 authorized courts of appeals judges. The courts of appeals are responsible for reviewing cases appealed from federal district courts (and in some cases from administrative agencies) within the boundaries of the circuit. A specialized appellate court came into existence in 1982 when Congress established the Federal Circuit, a jurisdictional rather than a geographic circuit. [2]

References:

Disclaimer: All material throughout this website is pertinent to people everywhere, and is being utilized in accordance with Fair Use.

[1]: United States Courts, “About the U.S. Courts of Appeals”: http://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure/about-us-courts-appeals

[2]: IIP Digital website: “History and Organization of the Federal Judicial System” (retrieved 2015): http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/publication/2008/05/20080522212957eaifas0.9853327.html#axzz47w7Cx0Fp

******************************************

Back to All Federal Courts

histories, purposes, and functions

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Simplified

All Federal Rules of Procedure Simplified

Like this website?

or donate via PayPal:

Disclaimer: Wild Willpower does not condone the actions of Maximilian Robespierre, however the above quote is excellent!

This website is being broadcast for First Amendment purposes courtesy of

Question(s)? Suggestion(s)?

[email protected].

We look forward to hearing from you!